Rivers and streams

Northland has a dense network of rivers and streams. None of them is considered major on a national scale.

Introduction

Northland's narrow land mass means most of our rivers are relatively short with small catchments. Most of the major rivers have their outlets into harbours, with only a few discharging directly to the coast. The Northern Wairoa River is Northland's largest river, draining a catchment area of 3650 square kilometres, or 29 percent of Northland's land area.

Rivers are channels for floodwaters, a function that is much needed with Northland's relatively high rainfall.

Rivers are ever changing because erosion is in progress all the time. Water action gradually breaks down rocks into smaller pieces and these are eventually carried downstream. The tiniest pieces become fine sediment which is washed out to sea - only for wave action in the ocean to deposit them back on land again as sand. The newly deposited material protects the coastline from eroding through wave action.

While this type of erosion is a natural process, human activities can change that. Water needs to have natural channels to dispose of floodwater. If buildings are put on natural floodplains, there can be problems with flooding. Drainage and irrigation activities can change natural river characteristics.

Northland's unstable hill country means many of the region's roads have been built on flood plains. Flooding on roads creates problems for transport.

Rivers and streams are rich environments for native plants, fish and insects, and provide important sources of water for people, industry and irrigation. Any contamination of fresh water has wide ranging effects all the way through the ecosystem around the river. A healthy river needs a healthy stream feeding into it. Pollution and sediment will all have an effect. Action to clean up a small stream will have positive effects all the way downstream to the sea.

Rivers and streams are also enjoyed for their beauty and for recreation activities such as swimming, kayaking, fishing and rafting. They are important drawcards for tourists as well.

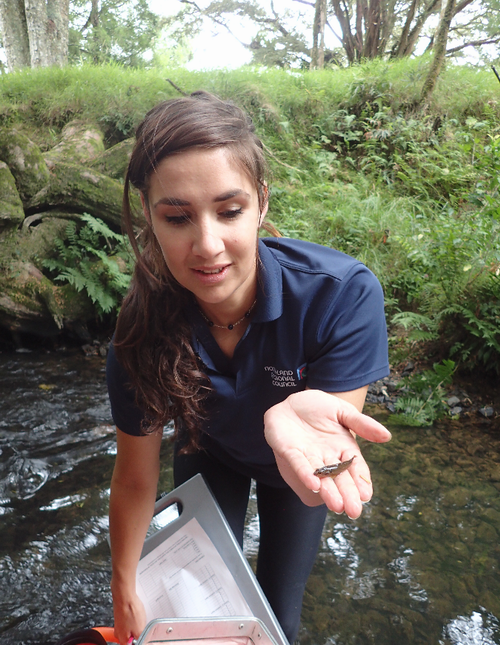

Learning about the importance of monitoring the health of our rivers.

Learning about the importance of monitoring the health of our rivers.

Northland Regional Council's role and policies

The Northland Regional Council (NRC) is responsible for the sustainable management of the region's natural and physical resources, including freshwater, soil, air quality and the coast. This means finding an appropriate balance between use of resources (such as water) and protecting the environment. The council is guided in looking after the region's rivers and streams by a number of laws including the Resource Management Act, the Soil Conservation and River Controls Act and the Land Drainage Act. The government can also direct how councils manage natural resources such as freshwater through national policy statements such as the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management.

Under the Resource Management Act, the council is required to develop a Regional Policy Statement – this identifies issues relating to resource management in Northland (including issues relating to water) and sets out what we aim to achieve and how we intend to achieve it.

We currently have three regional plans that are designed to look after the region's natural resources – the Air Quality Plan, the Coastal Plan and the Water and Soil Plan – these include policy and rules to manage each resource sustainably.

The Water and Soil Plan is the ‘rule’ book on how freshwater is managed. The Regional Water and Soil Plan contains detailed policies and rules that are designed to manage effects of activities on our rivers, lakes, groundwater and wetlands. Examples include rules and policy on taking water from a river, lake or groundwater, the draining of land and the disturbance to the beds of lakes and rivers and wetlands. It also contains rules and policy on land disturbance (such as vegetation clearance and earthworks), and discharges to land and water to protect water quality.

We have updated our three regional plans (including the Water and Soil Plan) and have combined them all into a new regional plan – see information about our Proposed Regional Plan. This new plan is still being finalised, but includes new policy and rules to manage freshwater (among other things) and reflects direction from the government in the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management. It includes allocation limits (the total volume of water that can be taken from a river, lake or groundwater) and minimum flows and levels (the amount of water that should be left in the waterbody). Like the Water and Soil Plan it also contains rules on activities in the beds of lakes and rivers (such as dams, removing gravel or building structures), protection of wetlands, land disturbance and discharges to land or water.

The council has also been working with community groups in five catchments around Northland to create Catchment Management Plans, which are designed to identify local solutions for freshwater related issues in each of the catchments. These plans have resulted in local rules that apply to each catchment and are included in the new regional plan.

The council plays an active role in managing flood risk and works with communities and district councils to find ways to reduce the risk to people and property. This includes mapping flood prone areas and undertaking flood reduction projects (such as detention dams, spillways and stop-banks). Our flood protection and natural hazard mapping information can be found in our Flood Protection & Natural Hazards section. This requires a good working relationship with district councils (which manage development such as subdivision and houses) and affected communities, so council has set up River Liaison Groups to assist in this process and to manage other river related issues (such as bank erosion and clearing debris/blockages). River management plans have been created for Kāeo, Kaihū, Hokianga, Whirinaki, Pakanae, Panguru, Pawarenga and the Awanui. Others will be created in time for other flood-prone areas.  The Kaeo flood risk reduction project aims to reduce the impacts of flooding on Kaeo township and its people.

The Kaeo flood risk reduction project aims to reduce the impacts of flooding on Kaeo township and its people.

Council also plays a role in land drainage – this includes applying rules to ensure land drainage activity does not make flood hazards worse, does not damage the environment, and does not compromise drainage works. In most cases, land drainage schemes are run by district councils (such as the Hikurangi Scheme) and are designed to maintain the productivity of land and / or redirect flood water away from property.

Helping landowners with soil conservation and to improve water quality is another large part of what we do – we have a team of Land Management Advisors that provides assistance / advice to landowners who want to stop erosion, or to improve water quality by fencing livestock out of rivers, planting river / lake margins or restoring wetlands. In many cases, council can assist with funding for such projects. More detail on our land management programmes can be found in the Land section on this website.

Northland rivers and streams

The types of rivers in Northland are influenced by the soil types they travel through on their journey to the ocean from high in the hills and ranges. The basin of land that drains into a river is called a water catchment. The size of the catchment is a factor in the size of the river that is created when all the water drains to the lowest point.

When rain comes, the large catchments and short rivers in Northland mean large volumes of water fill the valleys. Northland rivers tend to have a low normal flow but can rise very quickly with rain and cause flooding. However, flooding does not usually last long as the short rivers allow the water to drain quickly into the sea.

This map shows the main rivers in Northland and where they flow. Most of the rivers feed into harbours. Sometimes several rivers flow into one harbour.

Major catchments in Northland

Northern Wairoa River

The largest Northland river is the Northern Wairoa near Dargaville. It drains a catchment area of 3650 square kilometres. The Northern Wairoa occupies a drowned river valley system and is tidal for about 100km.

Rivers that contribute to the Northern Wairoa river are:

- Manganui River: The Manganui River drains a 409 square kilometre catchment of low rolling hill country, most of which is less than 150 metres above sea level, except for the northern boundary of the catchment which is formed by the Tangihua Ranges. The Manganui is slow flowing and meanders through swampy valleys subject to frequent flooding.

- Kaihū River: The Kaihū River drains 324 square kilometres north of Dargaville. It includes the western edge of the Tutāmoe Ranges back to the Tutāmoe settlement and the edge of the Waipoua Forest. It features a series of rocky gorges and waterfalls. Above Kaihū, the river flows over boulders.

- Awakino River: This river drains a catchment area of 116 square kilometres, including the western and southern slopes of Tutāmoe.

- Tangowahine River: The Tangowahine has a catchment of 125 square kilometres. It flows through a gorge at the northern end of the Mangaru Range and then opens out into a broad, easy valley.

- Kirikopuni River: The smallest river in the Northern Wairoa catchment is the Kirikopuni, which drains a narrow valley between the Mangaru Range and the Mangatipa River and Houto. The Kirikopuni frequently floods the whole valley floor.

- Mangakāhia River: The Mangakāhia River catchment covers about 800 square kilometres of central Northland, bounded by the Tutāmoe Range in the west and the Wairua River catchment in the east. It has the largest and most rapid flood discharge of any in the Northern Wairoa system.

- Wairua River: The Wairua River drains the north-eastern corner of the Northern Wairoa catchment via the Hikurangi Swamp. The large swamp was drained and turned into farmland in the 1970s. Once a lake bed, the swamp is susceptible to heavy rain storms from the north-east and a restricted outlet, making flooding common. The catchment covers 750 square kilometres.

Awanui River

The Awanui River and its tributaries drain the northern side of the Mangamuka Range and flow northwards through Kaitaia and across the Awanui flats to enter the Rangaunu Harbour at Unahi.

The tributaries, Te Puhi stream, Victoria River and Takahue River, are all fast-flowing mountain streams with gravel river beds in their upper reaches. Kaitaia sits on the floodplain at the point where the Awanui River is confined before spilling out on to an alluvial fan and the Awanui flats. Extensive drainage and flood control has been done to lessen the flood risk.

River bank protection work along the Awanui River will help reduce the risk of river flooding within the catchment.

River bank protection work along the Awanui River will help reduce the risk of river flooding within the catchment.

Kerikeri River

The Kerikeri River drains into Kerikeri Inlet from about 170 square kilometres of land. Streams in the catchment include Rangitane, Waipapa, Kerikeri and Puketōtara which drain east. Two smaller catchments, Wairoa and Okura, drain northward.

Kawakawa River

The catchment for the Kawakawa River covers about 820 square kilometres. Its northern boundary runs between Ōpua and Moerewa and its southern boundary is a low ridge separating it from the Hikurangi swamp catchment.

Waitangi River

With a catchment of 308 square kilometres, the Waitangi River draws water from most of the land between Kaikohe, south of Kerikeri and north of Moerewa. The Waitangi River flows into the Bay of Islands at Waitangi. A tributary, the Waiaruhe River, drains the Ngāwhā geothermal field near Kaikohe.

The Waitangi catchment ends as it flows over the Haruru Falls, and enters the Waitangi estuary.

The Waitangi catchment ends as it flows over the Haruru Falls, and enters the Waitangi estuary.

Waipū and Ruakaka Rivers

These two main rivers feeding into Bream Bay drain a total area of 310 square kilometres. Most of the river flowing to the Waipū River drains from the Brynderwyn Ranges in the south through the Ahouroa, Waionehu and Waihoihoi Rivers. The Ruakaka River flows in an easterly direction, draining an area half that of the Waipū river.

River catchments and water resources - online map

Our online water resources map includes river catchments, Northland aquifers, and monitoring sites around Northland. Use the legend icon to see the layers and symbols.

Go to our online water resources map

What lives in the river?

There are 27 native freshwater fish species and several marine species that occasionally wander into Northland rivers.

Native fish include eels, mullet, flounder and lamprey. They have to compete with three major introduced species: rainbow and brown trout, and perch.

Rivers are important for most of our native freshwater fish, which have a time when they migrate to the sea. Whitebait is one example. Their young are washed out to sea after hatching and then migrate back into streams from the sea in springtime.

Adult eels migrate to their spawning grounds in the Pacific Ocean. Juvenile eels (elvers) return to our streams and rivers during summer.

It is important that their way is not blocked by man-made structures such as dams, weirs or culverts.

Some native freshwater fish can climb through these obstacles to make it back to their traditional habitats upstream. But some cannot make the journey and stay in lower parts of the rivers.

One native freshwater fish, the grayling, has already become extinct. Consideration for the requirements of native freshwater fish is given in the design of any new structures. The Northland Regional Council requires the construction of a suitable "fish pass'' to enable the fish to travel along the waterway.

Types of native fish

Whitebait is not a type of fish - it is the juvenile stage of several native fish.

Inanga is the most common of the whitebait family.

Inanga is the most common of the whitebait family.

Whitebait can grow into any of five different types of native fish:

- Inanga is the most common of the family. It spawns in river margin vegetation that is flooded by extreme high tides.

- Short-jawed kokopu is extremely rare although it can be found in Northland.

- Banded kokopu prefer stony, bush-covered streams but can survive in weedy farmland streams.

- Giant kokopu is a large fish that can grow up to 58cm in length.

- Kaoro prefer fast-flowing, stony habitats in upper catchments.

This giant kokopu is eating a koura, native freshwater crayfish.

This giant kokopu is eating a koura, native freshwater crayfish.

Mudfish

The Northland/burgundy mudfish is unique to the region and found only in the Kerikeri/Kaikohe area, specifically near Kerikeri airport and Ngāwhā. Like the more common black mudfish, they live in wetlands, not rivers. They can survive for long periods burrowed deep in mud when the water in their pool dries up. Early settlers often found them in their swampy potato patches - the original fish and chips!

Another family of native fish is the bully, which lives in freshwater and the sea.

Redfinned bully is the most common and colourful of native fish. It spawns in freshwater but the juveniles are washed out to sea.

Male redfin bullies are our most colourful native fish, with bright orange-red fins.

Male redfin bullies are our most colourful native fish, with bright orange-red fins.

Bluegilled bully prefers swift-flowing rivers and high quality water and is the smallest of the bully family.

Crans bully is common in upper parts of streams. It is capable of living its entire life cycle in fresh water. The headwaters where it is found may be up to 70km - 80km from the ocean.

Giant bully is the largest of the family.

Torrentfish thrives in fast-flowing turbulent water, but can also be found in slower, meandering rivers. They are not good climbers.

Smelt are found in lower reaches of streams and rivers. Sometimes called the cucumber fish because of the strong "cucumber" smell when they are taken out of the water. They are not strong swimmers so they struggle in strong currents and cannot pass waterfalls or dams.

There are two types of eels and both are found in Northland. They are both excellent climbers. They have an excellent sense of smell and feed mostly at night. Eels can live for up to 60 or 70 years.

Shortfinned eel prefers slower moving streams and lakes.

Longfinned eel likes the upper reaches of streams.

Baby eels are called elvers.

Baby eels are called elvers.

Lamprey juveniles are found in river gravel for several years until they reach a length of 80-100 millimetres. At this stage they undergo a metamorphosis, changing their colour from mud-brown to blue. Their eyes appear and the dorsal fin grows. In winter, the lamprey migrate to the sea where they attach themselves to a host fish with their sucker-like mouth and begin to feed on the body fluids of the host. Several years later they migrate back into streams for spawning.

Koura, native freshwater crayfish, are widespread in Northland. New Zealand has two freshwater crayfish species, with one species being found throughout the North Island and the other along the Northern and West Coast of the South Island. Northland koura are slightly smaller (up to 70 millimetres long in streams) and also less robust and hairy than their southern cousins. Lengths of crayfish are greatest in lakes (to around 160 millimetres), with ages over three years not being uncommon. They are largely nocturnal in their habitat of lakes, streams, and wetlands, where they feed opportunistically on aquatic insects and vegetation. Freshwater crayfish are thought to function as a keystone species, with the modifications they make upon the environment permitting a greater range of species to exist than if they were not present. These crustaceans also provide an important food source for larger fish and waterfowl. All koura are non-migratory, and carry their eggs and then their developing young under their tails. Juveniles are released as perfect miniatures of the adult, able to fend for themselves immediately.

Koura provide an important food source for larger fish and waterfowl.

Koura provide an important food source for larger fish and waterfowl.

Numbers of all native species have been reduced because of many factors, including loss of habitat, water quality and competition from introduced fish species. Many wetlands have been drained for farmland - such as the Hikurangi Swamp near Whangārei.

The Wairua electric power station at Titoki, near Whangārei, has a trap and transfer system for fish which is mainly for elvers (young eels) migrating upstream, although other species are sometimes caught.

Some introduced fish eat whitebait - the young of native fish - so reduced numbers are surviving to become adults. They also compete for the same food as native fish. Others affect the habitat by burrowing into banks and affecting water quality.

The mosquito fish was introduced in the 1950s and 1970s to kill mosquito larvae - but unfortunately this fish is also a major competitor with native fish. The koi carp has been recently found in Northland. This fish has had a big impact in other parts of New Zealand because it undermines stopbanks by making burrows in the sides. Digging in the mud also affects water quality. The koi carp also competes with native fish for food.

Goldfish have ended up in many rivers in Northland, although they often don't keep the same gold colour once they breed in the wild. They can revert from their original colouring to olive or brown shades. Goldfish compete with native fish for food.

Importance to Māori

Rivers have spiritual significance to Māori as well as being a valuable food and water source for many marae.

To Māori, water is an essential ingredient, regarded as a taonga or treasure. It must be safeguarded for future generations.

Water is considered to possess a life force (mauri), and have a spirit (a wairua). To Māori, any discharge of contaminants into water, no matter how well purified in a treatment process, reduces the water's ability to sustain life. It thereby reduces its mauri, or life force.

Water is given different terms by Māori, according to its status.

Waiora is water in its purest form, usually rainwater, caught before it touches the earth. This water is used for ritual purposes.

Wai Māori is fresh water or drinking water from springs. It can be used for everyday purposes.

Waimate or Waikura is water that is stagnant or polluted, and is no longer capable of sustaining life.

Monitoring

Northland Regional Council scientists and other staff constantly monitor our rivers and streams for such things as pollution, chemical runoff, water levels and flow rates. This is done in a variety of ways. Sometimes samples of plant and animal life are taken which show how healthy a river or stream is. Water quality tests can give clues to what the likely sources of pollution are and where contamination might have come from. Water levels and flow rates show if floods could affect landowners.

Water quality tests can include the following:

Dissolved Oxygen (DO)

A healthy stream needs cool water and lots of dissolved oxygen to support a wide variety of creatures. Low oxygen levels may suffocate and kill fish and the many other creatures that live in streams and rivers.

Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD)

Pollutants such as milk or raw sewage break down very quickly when they enter a stream. The decomposition process requires a lot of oxygen. This could mean all the oxygen is removed from the water, killing all the creatures living in it.

Micro-organisms (bacteria and viruses)

Our staff test water for micro-organisms to ensure water is safe for swimming or shellfish collecting. Some micro-organisms can cause diseases in humans and animals. High levels of faecal material can indicate the possible presence of these bugs.

Temperature

Most creatures can survive in water temperatures ranging between 10 degrees celsius and 25 degrees celsius. If the temperature rises or falls outside this range, the creatures may die or move away.

Cool water contains the most dissolved oxygen, which is why trees planted along streams and rivers help keep streams healthy for fish and stream life.

Hot summer temperatures in Northland can heat the water to the point at which fish and other aquatic life have trouble breathing and may suffocate.

pH

The pH test for water checks the acidic or alkaline measurement. Pure water is 7 on the pH scale. Any major change from discharges of acid or alkaline substances can harm water life. Creatures prefer pH levels between 6.5 and 9.

Water clarity

Light penetration is important as it controls the amount of light in the water needed for aquatic plants to grow and allow aquatic animals, which are visual feeders, to find their food. Visual clarity indicates how much suspended sediment (soil) is in the water. Too much suspended sediment can harm fish and some macroinvertebrates by clogging their gills.

Nitrogen

Nitrogen is naturally occurring and is important for plant growth. It is a great fertiliser but too much of it can cause algal blooms. Two forms of nitrogen, nitrite-nitrogen and ammonia, become toxic at high concentrations and can cause direct harm to fish and macroinvertebrates.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus attaches to soil particles and is naturally present in water in low concentrations. Together with nitrogen, it is an essential nutrient for plant life. Too much can cause rapid weed growth or algal blooms which can choke aquatic life and cause long-term damage to the health of a stream, river, or lake. Much of the phosphorus in our rivers is a result of erosion and fertiliser use. Other sources include dairy factories, freezing works and sewage treatment plants.

Other tests

When staff know of a specific problem in an area, they may conduct other tests to gather evidence and detect sources. For example, ammonia tests might be conducted along with faecal coliform tests if it is suspected that septic tanks are failing in an area. Because ammonia is found in sewage less than 12 to 24 hours old, ammonia tests can help detect a recent sewage spill.

Monitoring these fish can tell us a lot about the health of the water.

Monitoring these fish can tell us a lot about the health of the water.

Floods and droughts

Localised heavy rain causing flooding is Northland’s biggest natural hazard risk.

High intensity rain from ex-tropical cyclones and other intense weather systems is a major feature of Northland’s rainfall.

Average amounts of rainfall soak into the soil, are taken up by trees and plants and run off the land to form Northland’s streams and rivers. Sometimes however, so much rain falls that rivers spill over their banks and flood adjacent land. Floods happen when the water and runoff is too much to be carried to the sea within river banks.

The water level in Northland rivers and streams is constantly changing, echoing in large part the amount of rain that’s recently fallen.

There are four main types of flood:

- Rising rivers can overflow their banks into the floodplain. A floodplain is the flat section next to a river and it can flood quite regularly.

- Flash floods happen when heavy rain falls in a small area with little warning.

- Coastal areas can sometimes flood because of unusually high tides or tsunami (tidal wave).

- Urban areas have a lot of concrete or hard surfaces which stop rainwater from soaking into the soil, so it is channelled into stormwater drains. Urban flash flooding occurs when the rain falls faster than the stormwater system can manage. These floods usually happen very quickly and can block roads and damage buildings. They don’t usually last very long.

Floodwaters can destroy land and wash away or damage roads, bridges and buildings. Crops can be flooded and livestock drowned. People’s lives are affected to varying degrees, sometimes significantly when large floods occur.

Major floods can cause a lot of damage and pollution from which it may take months or years to recover.

Sometimes intense rain can be experienced over small pockets of land, causing localised flooding, often with big impacts. Floods can cause hillsides and roads to slip, power cuts, stock losses and lead to people having to evacuate if their houses are in danger.

Flood damage is often worsened by large quantities of silt and debris in floodwaters.

Rainfall is typically plentiful all year round in Northland, but dry spells also occur - especially during summer and autumn. Drought can be a problem in Northland, affecting farmers, horticulturists and many others.

Northland Regional Council checks river use so water levels do not fall so low that they affect the health of a river or stream. This is particularly important during times of drought.

Farmers who have irrigation systems can be required to stop taking water from rivers once the water levels get too low. This helps protect aquatic life. The monitoring team takes between 100 and 120 stream flow gaugings during the summer. Automatic water quality instruments are also installed in some streams, providing continuous records.

Drought conditions could mean farmers have to stop taking water from rivers.

Drought conditions could mean farmers have to stop taking water from rivers.

Emergency Management

Northland Civil Defence plays an important emergency management role in the North. It keeps an around-the-clock eye on weather forecasters’ predictions and other information sources as part of being well prepared for flooding emergencies.

During storms and heavy rainfall, Northland Regional Council’s hydrology team provides key information to Northland Civil Defence about what’s happening with rising river levels.

The hydrology team also alerts farmers and others if there is danger from flooding along some Northland river systems. This helps people prepare for any danger and gives farmers time to move stock to higher ground.

The Northland Regional Council has set up 103 monitoring stations at different sites throughout Northland, collecting information every 15 minutes. The Whangārei branch of the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) operates another two water level recording sites.

Live cameras have been set up at some sites, such as Kāeo, Awanui and Otiria. These help people monitor rising water levels that can lead to flooding. You can see these at: www.nrc.govt.nz/webcams

The Kaeo webcam helps people monitor rising water levels during heavy rain events.

The Kaeo webcam helps people monitor rising water levels during heavy rain events.

The information gathered from these sites is sent automatically to the regional council office, which allows staff to offer an early warning system. The data is stored electronically, giving staff access to round-the-clock records at any time.

Preparation is perhaps the most important part of effective emergency management.

Northland Regional Council, Far North District Council, Whangarei District Council and Kaipara District Council are among more than 120 organisations that make up Northland Civil Defence. The Northland Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan at www.nrc.govt.nz/civildefenceplan provides these organisations with a regional framework for co-ordinating emergency services.

Being prepared helps reduce the impact of flooding on homes, schools and the wider community.

Flooding preparation tips:

- Check to see whether your local area has its own community response plan outlining what it will do if affected by flooding www.nrc.govt.nz/communityresponseplans

- Know what to do before, during and after flooding getready.govt.nz/emergency/floods

- Decide on what flood alerting options to use www.nrc.govt.nz/cdalert

- Make sure selected flood warning options are correctly set up

- Find out how much risk your house and school is at from flooding at www.nrc.govt.nz/floodmaps

- Fill out a household emergency plan for your house, school, etc. The GetReady website has household emergency plan information and a template for your plan at: getready.govt.nz/prepared/household/plan

- Make a flood evacuation plan – write down and display the plan

- Practise flood evacuation – check routes and time how long they take

- Put together and/or check getaway bags – including items to use at the evacuation assembly point

- Have a written list of important phone numbers in case phones are down

- Tell designated out-of-town contacts about your evacuation plans.

When facing immediate flooding, it’s important people head for higher ground and stay away from floodwater. Fast-moving floodwater – even if shallow - produces more force than most people realise.

For more tips about what to do before, during and after flooding, visit: getready.govt.nz/emergency/floods

Resource Consents

The demand for water is growing as Northlanders operate their homes and businesses, and more people move into the area. Anyone wishing to take water for any purpose other than household supply or stock watering may require a resource consent from the council.

This allows us to keep track of the demand on our water supply and make sure it is managed properly so it is sustainable.

A resource consent may be required before anyone can:

- discharge waste into water

- dam or divert a stream

- divert or discharge floodwaters

- build a bridge over a waterway

- take water other than for domestic use, and depending on the location of the take, for stock requirements; or

- take from groundwater.

Any of these activities can affect the water supply for other people, so the resource consent usually has conditions to control the way an activity is carried out. Some resource consents require regular monitoring. Often the consent holders choose to carry out monitoring themselves. This information is then checked regularly by council staff.

Consents usually specify how much water can be taken, and minimum river levels, so that the consent holder cannot take water during severe droughts. At such times, priority is always given to public water supplies ahead of non-essential uses like irrigation.

Municipal water supplies are the greatest user of water in Northland, accounting for more than half of the total volume of water allocated each year, or 0.14 billion cubic metres of water per year (m3/y). This supplies drinking water to Northland’s towns and city as well as supplying water to shops and factories.

Horticulture uses around 30 percent of the total volume of water allocated each year by resource consents, or 0.07 billion cubic metres. Most of the horticultural activities take place on the sandy soils in the far north, the fertile volcanic soils near Kerikeri and Whangārei, and on the sandy clay loam soils on the west coast near Dargaville.

What can you do?

The biggest threat to rivers and the wildlife that lives in them is the development of land for farming. Large sections of wetlands have been drained to make paddocks and large stretches of waterways have been exposed to the heat of the sun since riverside vegetation has been cleared. Direct access to rivers and streams for stock has led to the trampling and eroding of riverbanks and contamination of water with their waste.

Actions you can take include:

- spreading the word about native freshwater fish

- helping people understand the importance of habitats

- promoting the need to maintain wetlands

- promoting the importance of riverside planting

- advocating for the maintenance of unpolluted waterways

- joining a streamside care group

- keeping an eye out for problems on rivers such as logjams, erosion or flooding and alerting the council

- looking out for weeds that can cause problems include willows, privet, yellow ginger and walnut. Property owners can help by walking along riverbanks and pulling out these plants before they become a problem

- checking riverbanks for erosion after floods, and monitoring the changes; and

- letting the council know if you see cars dumped in waterways as they can be a pollution problem.

Environmental hotline

Regional council staff cannot be everywhere at once to keep an eye on Northland rivers and streams. We rely on people to help by reporting any pollution or problems. Our offices are in Whangārei, Kaitaia, Waipapa, Opua and Dargaville.

The council operates a toll-free Environmental Hotline 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to be used only for emergencies such as pollution spills.

The number for the environmental hotline is:

0800 504 639

Sources: Northland Regional Council staff; Water, Northland's Precious Resource, NRC booklet; Rivers and Us resource unit, NRC booklet; Schools in the Environment, No. 14; Department of Conservation.