Freshwater biodiversity and biosecurity

Freshwater is one of Northland's most precious resources. It is vital to life, including people, plants, and animals, it is a component of our social and cultural well-being, and it is vital to our region's industries.

Northland's lakes, rivers and streams provide habitat for native birds, fish, invertebrates and a wide range of aquatic and wetland plants. However, not all are healthy, and many have problems caused by increases in nutrient levels, sedimentation, stock access, invasive weeds, recreational use and land development. Coastal dune lakes are regarded as ‘globally imperilled' (at risk worldwide) because many are severely impacted by development and invasive weeds.

The biodiversity of our water is measured by the abundance and health of indigenous species and their ecosystems. Introduced species can negatively impact indigenous biodiversity and can make freshwater unusable. Biosecurity, which helps to keep introduced species out of the region or reduces their numbers, is important for the health of our freshwater systems.

Te Paki dune lake, Aupōuri Peninsula.

Te Paki dune lake, Aupōuri Peninsula.

What do we want for our freshwater ecosystems in Northland?

The operative Regional Policy Statement for Northland sets out what the council and community want – the objectives – for each natural and physical resource in our region. The objectives relating to freshwater biodiversity and biosecurity management are:

• Maintenance of the biodiversity of the Northland region;

• Protection of the life-supporting capacity of ecosystems through avoiding, remedying or mitigating (in that order of priority) the adverse effects of activities, substances and introduced species on the functioning of natural ecosystems;

• The maintenance or enhancement of the water quality of natural water bodies and coastal waters in Northland to be suitable, in the long-term, and after reasonable mixing of any contaminant with the receiving environment and disregarding the effects of any natural events, for aquatic ecosystems.

• Protection of areas of significant indigenous vegetation and the significant habitats of indigenous fauna.

The following are the anticipated environmental results after the policies for freshwater biodiversity and biosecurity management in the policy statement are carried out:

• Water quality to be suitable for aquatic ecosystems.

• Improved aquatic habitat.

• An increase in the areas of significant native vegetation and the significant habitats of formally protected native fauna.

• No significant increase in the number of threatened species in the region.

Note: the operative Regional Policy Statement is currently being reviewed. The proposed Regional Policy Statement (2013) is available at www.nrc.govt.nz/RPS

What is the state of our freshwater biodiversity?

Monitoring freshwater biodiversity is important for the management of fragile ecosystems and vulnerable species. Current monitoring carried out by the council includes macroinvertebrate sampling, fish monitoring, lake vegetation surveys, and river habitat assessments. Several new programmes are being developed to complement existing programmes.

Freshwater fish

Previous records show that 34 species of fish have been recorded in the region's waterways (see Table 36 in Appendix D), 18 of which are native species, 12 are introduced species and five are marine species venturing in freshwater habitats (NIWA: 2012).

According to the New Zealand Freshwater Fish Database, the most frequently recorded species in the region are the shortfin and longfin eels and the banded kōkopu.

Many of our native freshwater fish species are endemic to New Zealand, that is, they are not found anywhere else in the world, making them of significant importance to Northland, New Zealand and international freshwater biodiversity. For example, the Northland mudfish is only found in Northland and is classified as ‘nationally vulnerable' on the New Zealand threatened species list (Allibone et al: 2010).

Native eel (© Rohan Wells, NIWA).

Native eel (© Rohan Wells, NIWA).

Ten native fish species have been recorded in Northland lakes. The most common native species are the common bully and the shortfin eel. Other species, such as dwarf inanga and other dune lake galaxiids, are only found in the Kai Iwi and Poutō lakes in Northland, and in a few lakes on the southern head of the Kaipara Harbour. The giant kōkopu and the shortjaw kōkopu are also nationally uncommon, and have been recorded in a few locations in the region. These species are all classified as ‘declining' on the New Zealand threatened species list.

Banded kōkopu (© Rowan Strickland).

Banded kōkopu (© Rowan Strickland).

Fish monitoring in Lake Ōmāpere (a volcanic lake near Kaikohe) originally started in 2005 and is routinely carried out every two years. Since 2007, results have shown that the fish population has remained relatively stable. The native fish found in the lake were shortfin and longfin eels. Sadly the last recorded observation of common smelt was in 1997 (Gray: 2012) meaning it is probably now extinct from the lake.

The remaining catches included a range of introduced species, with species increasing over time (McGlynn: 2011).

While no routine fish monitoring is carried out, surveys are regularly conducted on specific species, such as threatened species. The Northland mudfish, classified as ‘nationally vulnerable', has been monitored since it was first discovered in 1998. Extensive survey work documenting the present distribution has indicated that this species may be one of New Zealand's rarest mudfish species (Department of Conservation: 2003).

Land development activities including the removal of vegetation and the draining of wetlands have restricted its distribution to a limited number of isolated wetlands in the area southwest of Kaikohe, to Kerikeri (Ling: 2009). In early 2004, a 10-year recovery plan was started by the Department of Conservation in order to reduce the decline of the Northland mudfish population

Freshwater invertebrates

Freshwater invertebrates are animals such as insects or molluscs that have no backbone (spinal column) and can be found in both lakes and rivers. Annual monitoring at the Regional River Water Quality Monitoring Network sites is conducted, primarily as an indicator of water quality. Together with fish monitoring in Lake Ōmāpere, the survey also records the presence of freshwater crayfish. There has been no record of them in the lake since the last survey, in 2008 (McGlynn: 2011). Freshwater mussels have also been recorded in the lake in a patchy distribution in high and stable numbers since 2007 (Gray: 2012). It is likely the mussels are improving the lake water quality due to the filtering service they provide (Gray: 2012).

A study of littoral macroinvertebrates in Aupōuri lakes in 2009, carried out by NorthTec, found that the invertebrate population was diverse and species-rich, dominated by insects and molluscs. However, the overall number of species and the number of those within each, varied considerably among the different lakes in the peninsula.

Several notable records were made during the survey. The most remarkable was the number of dragonfly species living in the lakes with up to five species observed, whereas most New Zealand lakes have only one species. Two of these five species are also found only in the North Island and were the most common species in the peninsula. There were also a lot of molluscs including numerous native Pea mussels and very large native snails (Ball et al: 2009).

Invertebrates such as mayflies, stoneflies, snails, freshwater shrimps, and mosquito and sand fly larvae, occur in Northland's rivers and streams. The taxonomic richness is an indicator recorded during surveys. It can be used to measure biodiversity and how the different communities within the environment are made up, by giving us the number of different taxa (biological groups) at each sampling site and describing the community structure (Pohe: 2011). In 2011, biodiversity ranged from just five species in the highly modified Paparoa Stream to a community rich in diversity in Waipoua River, with 34 species recorded.

Freshwater crayfish or koura.

Freshwater crayfish or koura.

Freshwater aquatic plants

Lake surveys have identified remarkable and nationally threatened native plants within Northland's largest lakes. A survey carried out by the National Institute for Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) in 33 lakes found a total of 65 aquatic plant species, 47 of which were native. The study also found five nationally endangered aquatic plant species (NIWA: 2002). Another survey conducted in 65 lakes found seven nationally endangered and four regionally rare plant species (Northland Regional Council: 2005).

Wetlands

A wetland is land that is covered in, or saturated by water, for at least some of the time. Wetlands occur in areas where surface water collects or where underground water seeps through to the surface. They include swamps, bogs, marshes, gumlands, saltmashes, mangroves and some river and lake edges.

In the past, wetlands in Northland covered around 258,451 hectares or 32 percent of the land area. Just 5.5% or 14,114ha of the original wetland area remains, with less than 4% remaining south of Kaitāia. Some of the wetlands being lost in Northland are unique and therefore irreplaceable (Northland Regional Council: 2011). For more information on wetlands refer to Chapter 3 – Biodiversity and biosecurity on land.

Lakes ecological value

NIWA conducts an annual survey of the major lakes in Northland to establish their ecological status. However, there are some 400 lakes recorded in Northland and therefore it is important to understand that the information reported does not intend to reflect the state of all regional lakes.

Lakes in the programme are ranked according to their ecological value, that is, how many native or endangered plant and animal species they contain, the absence of pest species and how close the lake is to its natural state (Northland Regional Council: 2011). For more information visit www.nrc.govt.nz/lakedata

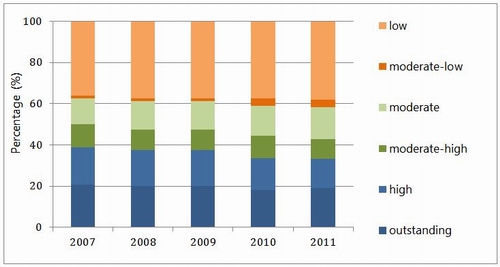

Between 2007 and 2011, NIWA staff surveyed 85 lakes and ranked them based on the assessments mentioned above. The rankings from best to worst are: outstanding, high, moderate to high, moderate, low to moderate and low. Figure 76 shows the evolution over time of the percentage of lakes in the different ranks.

Figure 76: Percentage of lakes in the different ecological value rank over time (NIWA 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011)

Results show that even if no major change is occurring over time, the number of lakes falling into the lower ecological value rankings is increasing. Between 2007 and 2011, the proportion of lakes monitored with low ecological value rank went from 36 to 38%, lakes with moderate-low rank went from 1-4%, and with moderate rank went from 12-15%. As a consequence, the number of lakes falling into the higher ecological value rank is decreasing and remarkable biodiversity features are increasingly at risk of disappearing.

It is commonly known that Northland has some of New Zealand's highest ranked examples of intact natural aquatic ecosystems with some lakes populated with totally native vegetation. Northland is also considered the region with the largest concentration of exceptional lakes in the North Island (NIWA: 2002, 2011). This highlights the need for vigilance to prevent the spread of weeds and introduced fish species into new lakes and the adequate protection of our waterways.

What are the issues affecting freshwater biodiversity in Northland?

Pollution, sedimentation, habitat loss and fragmentation

Pollution of waterways can be caused by various activities in both urban and rural areas. At a national level, farming is regarded as being the principal source of nitrogen in New Zealand waterways. Excessive levels of nitrogen and phosphorus can cause algal blooms and extensive plant growths, which impact on the aquatic ecosystem.

The two most common chemical forms of nitrogen found in water are ammonia and nitrate, whereas phosphorus mainly exists as phosphate. While both ammonia and nitrate are highly soluble in water, phosphate usually sticks to soil and sediment. High sediment volumes released in waterways are another source of pollution, which can impact freshwater biodiversity. Erosion is a natural process however some activities, such as intensive pastoral farming, activities on erosion-prone land, and inappropriately managed earthworks, can increase erosion rates.

Habitat loss is frequently associated with, but not limited to, changes in surrounding land use including land clearance, wetland drainage and reclamations. As human activities break up large connecting areas of native habitat, they become more vulnerable to damage from pests, diseases and environmental influences and their biodiversity values can decrease. More intensive land use frequently involves clearing regenerating vegetation areas, which also act as a buffer and increase the value of neighbouring areas of more mature forest. Subdivision of land can also lead to fragmentation when properties are developed.

Pest plants and animals

Freshwater ecosystems face many pressures which can make them even more vulnerable to invasion by animal and plant pests and therefore result in habitat loss.

Aquatic pests can be hard to detect, more so than pests on land, and can easily spread throughout connected waterways. As a result, pest control is a challenging exercise, alongside the fact that a limited number of management tools are currently available to achieve this demanding task.

What are the main freshwater pest species in Northland?

Submerged aquatic weeds

Freshwater weeds can form dense mats, completely smothering waterways and badly affecting water quality. These mats can also kill native plants, block drains causing flooding, and disrupt recreation activities. Freshwater weeds are usually fast growing, robust and able to tolerate a broad range of environmental conditions and habitats. Most will grow from small pieces of stem and are easily transported to new places by people, diggers, boats, equipment, and even birds.

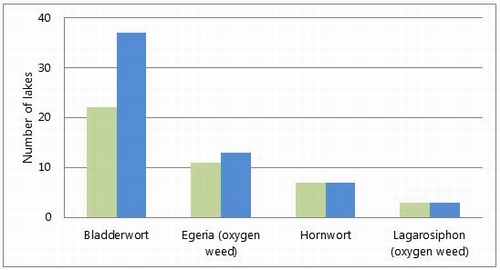

Four main aquatic pest plant species are present in Northland's waterways:

• Hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum) is currently considered the worst submerged weed in New Zealand as it can grow from the water's edge to depths greater than 15 metres and can displace all submerged vegetation, including other weed species. Hornwort is found in seven Northland lakes, most of which are on the Aupōuri Peninsula.

• Bladderwort (Utricularia gibba) is the most widespread aquatic weed species in Northland. It was first recorded in one lake in 1999. By 2006, it had spread to 22 lakes, and to most of the region by 2011 (Figure 78), including the Kai Iwi lakes.

Bladderwort is free-floating and forms thick submerged mats, covering other plant species. It rarely grows below 3m deep and prefers shallower, less exposed water bodies. In larger lakes the main impacts appear to be in the zone sheltered by emergent sedges. Unfortunately, this is also the preferred habitat of the native bladderwort (Utricularia australis), which is classified as nationally endangered. There are no control tools currently available for bladderwort.

• The oxygen weeds egeria (Egeria densa) and lagarosiphon (Lagarosiphon major), are a major threat to shallow, nutrient-rich water bodies where they can grow over the entire water body, eventually collapsing and switching the lake from a macrophyte-dominated to an algal-dominated lake. Lagarosiphon is only found in two lakes on the Aupōuri Peninsula and one lake on the Poutō Peninsula. Egeria is found in 13 Northland lakes, mainly in the Aupōuri and Poutō areas (NIWA: 2011).

Figure 77: Number of lakes with the invasive weed species bladderwort, egeria, hornwort or lagarosiphon, recorded in 2006 (green bar) and 2011 (blue bar)

A diver surveying a 4m tall hornwort in Lake Heather (©NIWA).

A diver surveying a 4m tall hornwort in Lake Heather (©NIWA).

Animal pests

Freshwater animal pests can also have a negative effect on water quality and native plant and animal communities. They can stir up sediment and make water murky, increase nutrient levels and algal concentrations, and contribute to erosion. These pests may feed on and remove aquatic plants, or prey on invertebrates, native fish and their eggs. They also compete with native species for food and space.

There are a number of introduced pest fish species including koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), perch (Perca fluviatilis), tench (Tinca tinca), brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus) and rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus) that are present in Northland. Some of these have been illegally introduced, others introduced for the purposes of coarse fishing and for ornamental purposes. Rudd and catfish are the most widespread in Northland but currently are not common in the region's high value waterways.

Gambusia (Gambusia affinis, also known as mosquito fish) is by far the most widely distributed pest fish in Northland, and is widespread throughout the region. Gambusia populations quickly expand to out-number other fish species. Although small, they are very aggressive and attack some native species by nipping at their fins and eyes and preying on their eggs.

A brown bullhead catfish from Lake Ōmāpere.

A brown bullhead catfish from Lake Ōmāpere.

What is being done?

The council is currently seeking technical advice to develop and carry out an up to date, comprehensive regional strategy for the management of Northland's unique lakes resource. This will combine management of water quality, biodiversity values and biosecurity of Northland lakes and their catchments. A system to prioritise lakes, based on these and other key criteria, will be developed and form the basis for regional management.

Tools in the toolbox

Pest management strategies

Control methods for freshwater pests are currently very limited, and pest species are difficult to remove once established. Preventing or minimising the spread of freshwater pests is a very important part of protecting Northland's natural aquatic ecosystems.

The Northland Regional Pest Management Strategies 2010-2015 include 17 freshwater plants and 12 freshwater animals of concern. These pests fall under different classifications in the strategies, depending on whether they are currently found in the region and how widespread they are. This classification helps guide the objectives, operational plans and management programmes for each pest. The main pest management methods include education, surveillance and response.

The council aims to raise public awareness of freshwater pests by providing information about them, their impacts and management options through publicity campaigns, publications, and events, and by providing an advice and identification service. The council also works with partners from the Ministry for Primary Industries and the Department of Conservation to deliver a summer "Check, Clean, Dry" programme aimed at preventing the spread of freshwater pests.

Targeted freshwater weed surveillance is carried out in seven high priority lakes, and an additional 8-12 lakes, during the ecological assessment surveys each year. The lakes in the targeted surveillance programme have been selected based on the risks and the likely impacts of invasive species being introduced. Finding out where pest species can access the lakes allows for targeted searches of the high risk areas within each.

One of the benefits of surveillance and increased public awareness is that it increases the likelihood of early detection of pests. However, in order to respond rapidly and appropriately, plans need to be in place. These plans will be developed as part of the new lakes' management strategy.

Other tools

Where a freshwater weed is found early, it's possible to remove small infestations by hand weeding, or covering the weeds with compression screens of weighted down weed mat. Other options currently include the use of specialised herbicides or the biological control agent, grass carp.

The council has worked closely with landowners, local communities and iwi to release grass carp into two Northland lakes, Lake Roto-otuauru (Swan) and Lake Heather. The grass carp were introduced as part of restoration programmes aimed at eradicating the aquatic weeds hornwort and egeria from the lakes and reducing the risk of these weeds spreading to nearby high-value lakes. The grass carp were introduced to Lake Roto-otuauru in May 2009 and to Lake Heather in June 2010.

Grass carp release into Lake Roto-otuauru (Swan).

Grass carp release into Lake Roto-otuauru (Swan).

Progress with the eradication of hornwort and egeria from these lakes has been rapid with nearly all traces of these weeds removed in two to three years. The risk of transfer of these weeds to neighbouring high value lakes is now near zero. The fish are expected to remain in the lakes for a total of five years. It is important that no fragments of weed remain in the lakes, as they could regrow once the fish are removed. It's expected that native aquatic plants will regrow from seed in the lake sediments once the fish are removed.

Herbicides approved for use in water are currently limited, but can be an effective control option. Endothall is the most effective herbicide permitted for aquatic use in New Zealand and is extremely selective, only killing three aquatic weed species. Native plant species are unaffected or suffer only minor damage. The council is working closely with landowners and local iwi, and will be using endothall to eradicate the oxygen weed lagarosiphon, from Lake Phoebe on the Poutō Peninsula, in 2012. The lake is the only known site of lagarosiphon in this area, and the weed eradication is part of a lake restoration programme which also aims to reduce the risk of this weed spreading to nearby high-value lakes.

Monitoring

The council – alongside other organisations and contributors – currently monitors fish, macroinvertebrates, aquatic plants and wetlands.

Fish monitoring in Northland is currently restricted to:

• Rare species such as the Northland mudfish, dwarf inanga and other dune lake galaxiids, and short jaw kōkopu, mostly by the Department of Conservation in line with recovery plans. Northtec also monitors mudfish at a few locations in Northland.

• Presence/absence monitoring by consent applicants for environmental impact assessment reports, to gather background information for resource consent applications.

• A pilot study investigating species richness at eight selected sites within the council's River Water Quality Monitoring Network. This programme is still under development.

Macroinvertebrates are monitored every year at each river quality monitoring site and primarily used as a water quality indicator. Other surveys, such as the annual survey conducted in Lake Ōmāpere, also record macroinvertebrates in regional lakes.

NIWA (with help from the council and the Department of Conservation) monitors freshwater aquatic plants in 85 lakes – on a rotational basis – every year including Aupōuri, Karikari, Kai-Iwi and Poutō areas. This survey also assesses the ecological value of each lake and provides further information on native species and therefore on lake environmental health.

The wetlands' monitoring programme uses national standards (Wetland Condition Index) and is carried out at approximately 15 wetlands, which have received funding through the council's Environment Fund.

Top wetlands project

In 2009 the council initiated the Top Wetlands Project. Since then more than 900 of Northland's remaining wetlands have been added to a Geographical Information System-linked database and 304 of the region's best and most irreplaceable wetlands were ranked and prioritised for management and protection using a scoring system based on national methods.

More than 40 of Northland's estuarine wetland systems were scored and ranked separately. The next phase of the project involves working with the landowners of high value ranked wetlands (153 sites to date) to provide information about their wetlands and to offer assistance and advice on how to care for them (Northland Regional Council: 2011). For more information about the project go to: www.nrc.govt.nz/wetlands

How are we measuring up against our objectives?

An increase in the areas of significant indigenous vegetation and the significant habitats of indigenous fauna which are formally protected

• The non-statutory approaches to biodiversity management are working well. The Northland Biodiversity Enhancement Group is a good example of inter-agency co-operation on an informal level and there are over 50 active environmental land care groups in the region. Northland has also seen a significant increase in council funds available, such as the Environment Fund and the Significant Natural Areas Fund (Far North District Council). Whāngārei District Council and Kaipara District Council also have funds available, which includes funding for freshwater restoration projects.

• The regional council is making progress with identifying the best wetlands across the region. More ecological districts have now been surveyed and most of the 19 ecological districts have published reports. There are also a large number of landowners carrying out active biosecurity management and biodiversity enhancement on their properties, throughout Northland.

No significant increase in the number of threatened species in the region

• Northland continues to lose significant indigenous wetland and species through human activities, such as land drainage. The regional council is currently completing a database of these wetlands and it is anticipated this will help us work out how much native wetland has been lost over time. The database will also help to identify and protect the existing significant native wetlands.

• The identification of biodiversity values is happening slowly. Sites of Significant Biological Interest are not yet identified across the region. The sharing of information is not always consistent between agencies. There are few rules in the regional plans to protect freshwater biodiversity, because of a lack of clear statutory role for the regional council when the plans were developed.

Appendix D

Table 36: Freshwater fish recorded in Northland on the New Zealand Freshwater Fish Database

| Scientific name | Common name | No. of records |

| Native fish | ||

| Anguilla australis | Shortfin eel | 344 |

| Anguilla dieffenbachii | Longfin eel | 320 |

| Cheimarrichthys fosteri | Torrentfish | 90 |

| Galaxias argenteus | Giant kōkopu | 1 |

| Galaxias brevipinnis | Koaro | 24 |

| Galaxias fasciatus | Banded kōkopu | 295 |

| Galaxias gracilis | Dwarf inanga | 24 |

| Galaxias maculatus | Inanga | 218 |

| Galaxias postvectis | Shortjaw kōkopu | 17 |

| Geotria australis | Lamprey | 9 |

| Gobiomorphus basalis | Crans bully | 81 |

| Gobiomorphus cotidianus | Common bully | 263 |

| Gobiomorphus gobioides | Giant bully | 74 |

| Gobiomorphus hubbsi | Bluegill bully | 10 |

| Gobiomorphus huttoni | Redfin bully | 238 |

| Neochanna diversus | Black mudfish | 75 |

| Neochanna heleios | Northland mudfish | 51 |

| Retropinna retropinna | Common smelt | 108 |

| Total number of records | 2438 | |

| Exotic fish | ||

| Ameiurus nebulosus | Catfish | 10 |

| Carassius auratus | Goldfish | 27 |

| Ctenopharyngodon idella | Grass carp | 2 |

| Cyprinus carpio | Koi carp | 11 |

| Gambusia affinis | Gambusia | 160 |

| Hypophthalmichthys molitrix | Silver carp | 1 |

| Oncorhynchus mykiss | Rainbow trout | 28 |

| Oncorhynchus tshawytscha | Chinook salmon | 1 |

| Perca fluviatilis | Perch | 1 |

| Salmo trutta | Brown trout | 9 |

| Scardinius erythrophthalmus | Rudd | 13 |

| Tinca tinca | Tench | 4 |

| Total number of records | 269 | |

| Estuarine/marine species | ||

| Aldrichetta forsteri | Yelloweyed mullet | 8 |

| Grahamina sp. | Estuarine triplefin | 22 |

| Mugil cephalus | Grey mullet | 21 |

| Parioglossus marginalis | Dart goby | 3 |

| Rhombosolea sp. | Flounders | 1 |

| Total number of records | 26 | |

| Paranephrops | Koura | 248 |

| No species recorded | 137 |

References

NIWA (2012). New Zealand Freshwater Fish Database 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.niwa.co.nz/our-services/online-services/freshwater-fish-database

Information on categories of the New Zealand threatened species list: https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/biodiversity/biodiversity-new-zealand-resources/biodiversity-references/species/

Gray, T. (2012). Review of the Lake Ōmāpere Restoration and Management Project. Report prepared for Northland Regional Council. TEC Services.

McGlynn, M. (2011). Freshwater Fish Survey, Lake Ōmāpere, Northland – November 2011. Field survey report for Northland Regional Council.

Department of Conservation (2003): New Zealand mudfish (Neochanna spp.) recovery plan 2003–13. Threatened Species Recovery Plan 51. Wellington, p25.

Ling, N. (2009). Proposed monitoring of Northland mudfish (Neochanna heleios) in the Waitangi Forest wetlands: effects of increased sewage effluent discharge. CBER Contract Report 108. Client Report prepared for Department of Conservation. University of Waikato, Hamilton, pp10.

Ball, O. J. P., Pohe, S. R. & Winterbourn, M. J. (2009). The littoral macroinvertebrate fauna of 17 dune lakes on the Aupouri Peninsula, Northland. Unpublished report prepared by NorthTec (Environmental Sciences Department) for Northland Regional Council. Foundation for Research, Science and Technology Envirolink Grant: 681-NLRC-96, p36.

Pohe, S.R. (2011). Northland Macroinvertebrate Monitoring Programme: 2011 monitoring report. Unpublished report prepared by Pohe Environmental for Northland Regional Council, p40.

NIWA (2002). The Aquatic Vegetation of 33 Northland Lakes. NIWA: Hamilton.

Northland Regional Council (2005). Annual Monitoring Report 2004-2005. Northland Regional Council, Whāngārei.

Northland Regional Council (2011). Annual Monitoring Report 2010-2011. Northland Regional Council, Whāngārei.

Northland Regional Council (2011). Annual Monitoring Report 2010-2011. Northland Regional Council, Whāngārei.

Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (2012). Water Quality in New Zealand: Understanding the Science. Wellington: Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment.

NIWA (2011). Northland Lakes Ecological Status 2011. NIWA, Hamilton.